Ring Species

Copyright © 2020 C.E. by Dustin Jon Scott

Introduction

Ring species push the boundaries of the biological species concept, and as such are an important idea to understand both in ecology and evolutionary biology, even if real-life examples are relatively few and far between. Part of the reason for their importance is that they demonstrate what appear to be speciation events in multiple extant stages, in that they show populations slowly becoming less interfertile with one another in space via residual populations representing how the non-interfertile populations became that way over time. If you’ve ever heard someone ask, “if people came from monkeys, why aren’t monkeys still becoming people; why aren’t there all different stages of monkey-men alive in the world today?”, ring species provide an example, essentially, of what it would be like to still have “monkey men” (or rather the equivalent thereof as applicable to other speciation events) surviving until the present day.

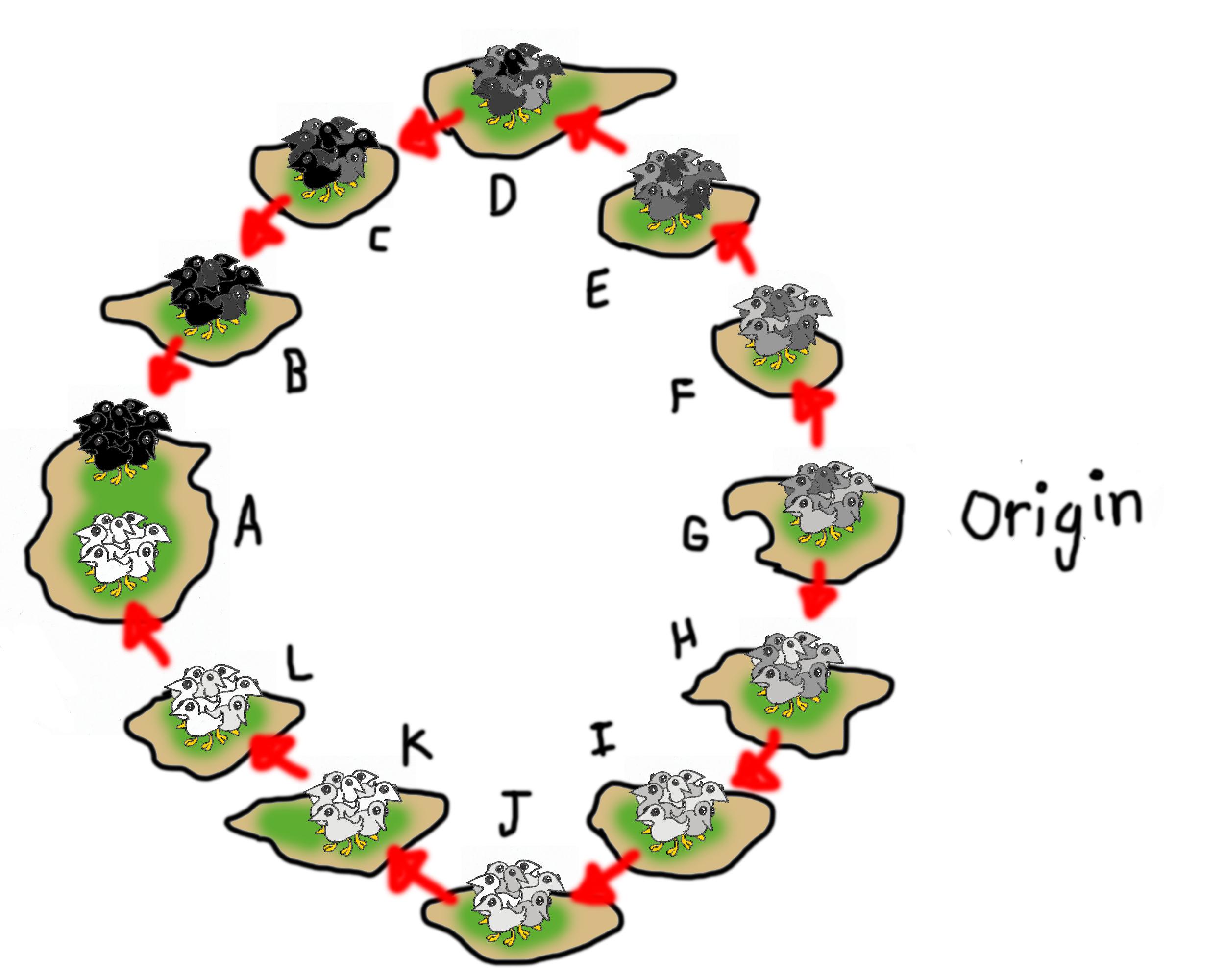

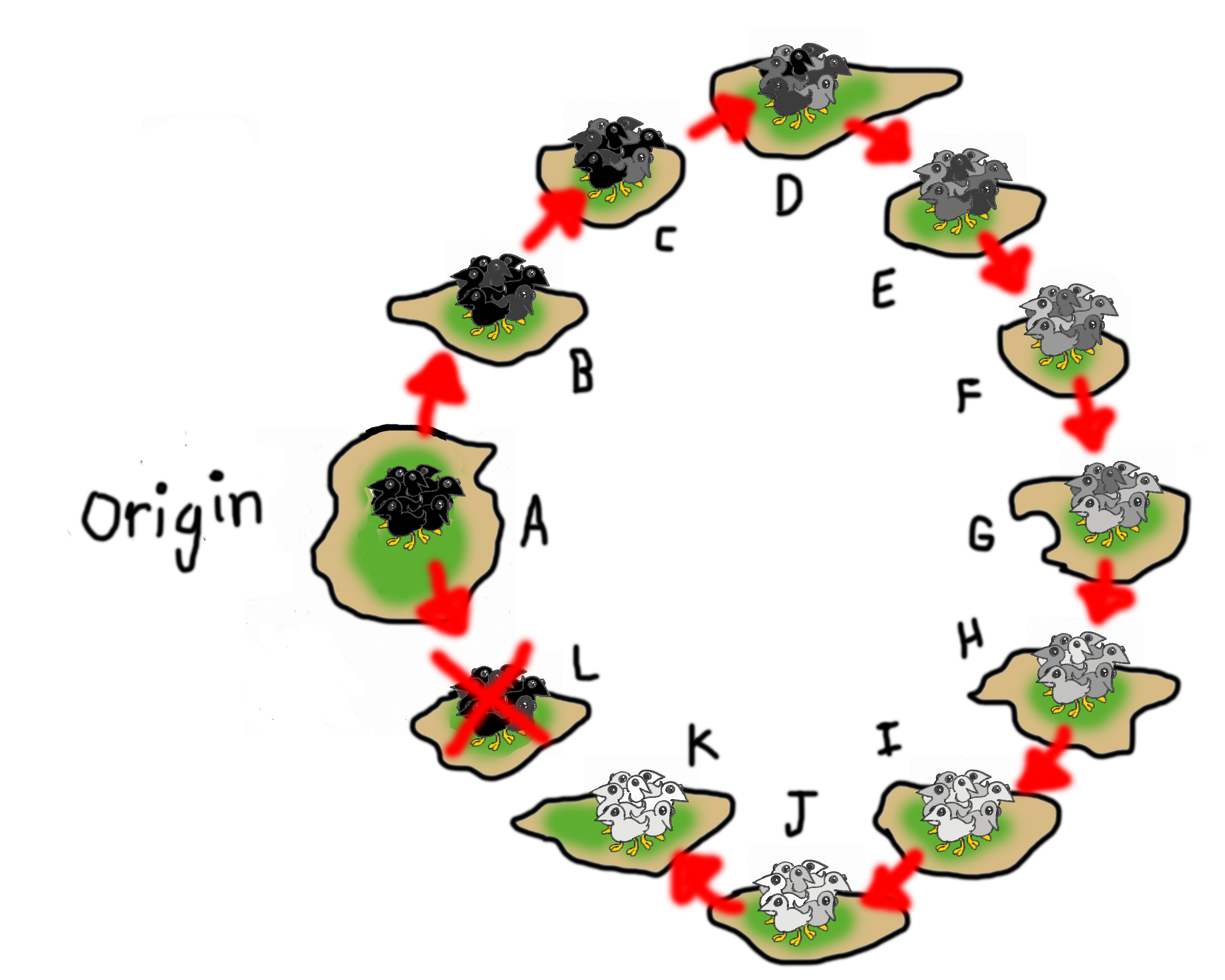

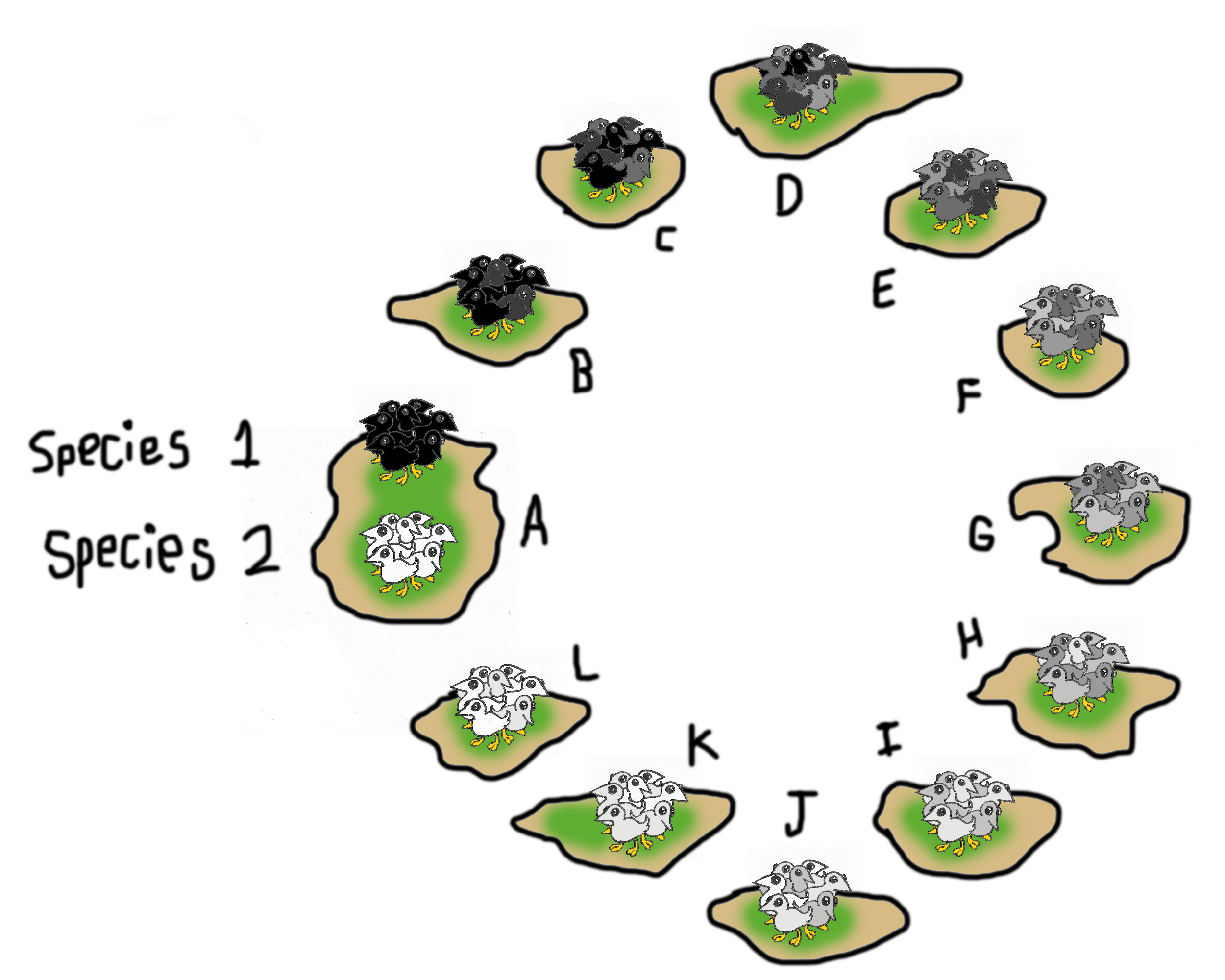

Let’s suppose you come upon an island, called Island A, upon which there appear to be two very similar species of bird: one black (Species 1), one white (Species 2). Though they seem closely related, Species 1 and Species 2 are unable to breed with one another. You decide to study Species 1, which you quickly discover also exists on another island in the island chain. You study the population of Species 1 living on Island B, and discover that some individuals are not black but instead a dark grey. Then as you move to Island C, you notice that most are a dark grey, with only a few true black birds and some a slightly less-dark grey. On Island D you find even more less-dark grey birds and even fewer black ones. On Island E, most are the less-dark grey, with only a few darker grey ones, no true black ones, and even a few medium grey birds. You keep going from island to island, noticing Species 1 keeps getting lighter in color. On Island G they're mostly medium grey, with some dark grey birds and some light grey birds. Island K has mostly light grey birds. Island L has mostly white birds with only a couple of light grey ones. By the time you get back around to Island A, you realize the birds you're studying aren’t Species 1 at all; you're now studying Species 2, the white birds who can’t interbreed with the black ones. Yet, before you got back around to Island A, every population of birds you studied was able to breed with its neighboring populations.

Formation of Ring Speces

Ring species can form when an initial population radiates outward, but some of the subsequent populations are prevented from breeding with one another. It’s basically when a very simple, allopatric speciation event occurs yet the ancestral populations do not go extinct.